Index

- Guessing Game

- Common Programming Concepts

- Understanding Ownership

- Using Structs

- Enums and Pattern Matching

- Managing Growing Projects with Packages, Crates, and Modules

- Defining Modules to Control Scope and Privacy

- Paths for Referring to an Item in the Module Tree

- Bringing Paths into Scope with the use Keyword

- Separating Modules into Different Files

- Common Collections

- Error Handling

- Generic Types, Traits, and Lifetimes

- Writing Automated Tests

- Object Oriented Programming

- Adding dependancies

- Option Take

- RefCell

- mem

- Data Structure

- Recipe

- Semi colon

- Calling rust from python

- Default

- Crytocurrency With rust

- Function chaining

- Question Mark Operator

- Tests with println

- lib and bin

- Append vector to hash map

- Random Number

- uuid4

- uwrap and option

- Blockchain with Rust

- Near Protocol

- Actix-web

Enums and Pattern Matching

Defining an Enum

enum IpAddrKind {

V4,

V6,

}

V4,

V6,

}

IpAddrKind is now a custom data type that we can use elsewhere in our code.Enum Values

We can create instances of each of the two variants of

IpAddrKind like this: let four = IpAddrKind::V4;

let six = IpAddrKind::V6;

let six = IpAddrKind::V6;

We can then, for instance, define a function that takes any

IpAddrKind:fn route(ip_kind: IpAddrKind) {}

And we can call this function with either variant:

route(IpAddrKind::V4);

route(IpAddrKind::V6);

route(IpAddrKind::V6);

Using enums has even more advantages. Thinking more about our IP address type, at the moment we don’t have a way to store the actual IP address data; we only know what kind it is.

enum IpAddrKind {

V4,

V6,

}

struct IpAddr {

kind: IpAddrKind,

address: String,

}

let home = IpAddr {

kind: IpAddrKind::V4,

address: String::from("127.0.0.1"),

};

let loopback = IpAddr {

kind: IpAddrKind::V6,

address: String::from("::1"),

};

V4,

V6,

}

struct IpAddr {

kind: IpAddrKind,

address: String,

}

let home = IpAddr {

kind: IpAddrKind::V4,

address: String::from("127.0.0.1"),

};

let loopback = IpAddr {

kind: IpAddrKind::V6,

address: String::from("::1"),

};

We can represent the same concept in a more concise way using just an enum, rather than an enum inside a struct, by putting data directly into each enum variant. This new definition of the

IpAddr enum says that both V4 and V6 variants will have associated String values:enum IpAddr {

V4(String),

V6(String),

}

let home = IpAddr::V4(String::from("127.0.0.1"));

let loopback = IpAddr::V6(String::from("::1"));

V4(String),

V6(String),

}

let home = IpAddr::V4(String::from("127.0.0.1"));

let loopback = IpAddr::V6(String::from("::1"));

If we wanted to store

V4 addresses as four u8 values but still express V6 addresses as one String valuefn main() {

enum IpAddr {

V4(u8, u8, u8, u8),

V6(String),

}

let home = IpAddr::V4(127, 0, 0, 1);

let loopback = IpAddr::V6(String::from("::1"));

}

enum IpAddr {

V4(u8, u8, u8, u8),

V6(String),

}

let home = IpAddr::V4(127, 0, 0, 1);

let loopback = IpAddr::V6(String::from("::1"));

}

struct Ipv4Addr {

// --snip--

}

struct Ipv6Addr {

// --snip--

}

enum IpAddr {

V4(Ipv4Addr),

V6(Ipv6Addr),

}

This code illustrates that you can put any kind of data inside an enum variant: strings, numeric types, or structs, for example. You can even include another enum! Also, standard library types are often not much more complicated than what you might come up with.

A

Message enum whose variants each store different amounts and types of valuesenum Message {

Quit,

Move { x: i32, y: i32 },

Write(String),

ChangeColor(i32, i32, i32),

}

Quit,

Move { x: i32, y: i32 },

Write(String),

ChangeColor(i32, i32, i32),

}

This enum has four variants with different types:

•

Quit has no data associated with it at all.•

Move includes an anonymous struct inside it.•

Write includes a single String.•

ChangeColor includes three i32 values.The following structs could hold the same data that the preceding enum variants hold:

struct QuitMessage; // unit struct

struct MoveMessage {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

struct WriteMessage(String); // tuple struct

struct ChangeColorMessage(i32, i32, i32); // tuple struct

struct MoveMessage {

x: i32,

y: i32,

}

struct WriteMessage(String); // tuple struct

struct ChangeColorMessage(i32, i32, i32); // tuple struct

There is one more similarity between enums and structs: just as we’re able to define methods on structs using

impl, we’re also able to define methods on enums. Here’s a method named call that we could define on our Message enum:fn main() {

enum Message {

Quit,

Move { x: i32, y: i32 },

Write(String),

ChangeColor(i32, i32, i32),

}

impl Message {

fn call(&self) {

// method body would be defined here

}

}

let m = Message::Write(String::from("hello"));

m.call();

}

enum Message {

Quit,

Move { x: i32, y: i32 },

Write(String),

ChangeColor(i32, i32, i32),

}

impl Message {

fn call(&self) {

// method body would be defined here

}

}

let m = Message::Write(String::from("hello"));

m.call();

}

The Option Enum and Its Advantages Over Null Values

The concept that null is trying to express is still a useful one: a null is a value that is currently invalid or absent for some reason.

Rust does not have nulls, but it does have an enum that can encode the concept of a value being present or absent. This enum is Option<T>, and it is defined by the standard library as follows:

enum Option<T> {

Some(T),

None,

}

Some(T),

None,

}

The

Option<T> enum is so useful that it’s even included in the prelude; you don’t need to bring it into scope explicitly. In addition, so are its variants: you can use Some and None directly without the Option:: prefix. The

<T> syntax is a feature of Rust we haven’t talked about yet. It’s a generic type parameterFor now, all you need to know is that

<T> means the Some variant of the Option enum can hold one piece of data of any type. let some_number = Some(5);

let some_string = Some("a string");

let absent_number: Option<i32> = None;

let some_string = Some("a string");

let absent_number: Option<i32> = None;

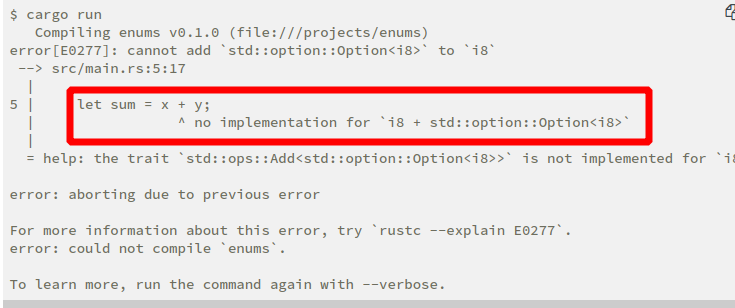

Error code:

fn main() {

let x: i8 = 5;

let y: Option<i8> = Some(5);

let sum = x + y;

}

let x: i8 = 5;

let y: Option<i8> = Some(5);

let sum = x + y;

}

In other words, you have to convert an

Option<T> to a T before you can perform T operations with it.Other examples:

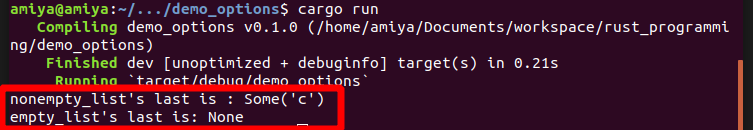

fn main() {

let nonempyt_list = vec!['a', 'b', 'c'];

println!("nonempty_list's last is : {:?}", nonempyt_list.last());

let empty_list: Vec<char> = vec![];

println!("empty_list's last is: {:?}", empty_list.last());

}

let nonempyt_list = vec!['a', 'b', 'c'];

println!("nonempty_list's last is : {:?}", nonempyt_list.last());

let empty_list: Vec<char> = vec![];

println!("empty_list's last is: {:?}", empty_list.last());

}